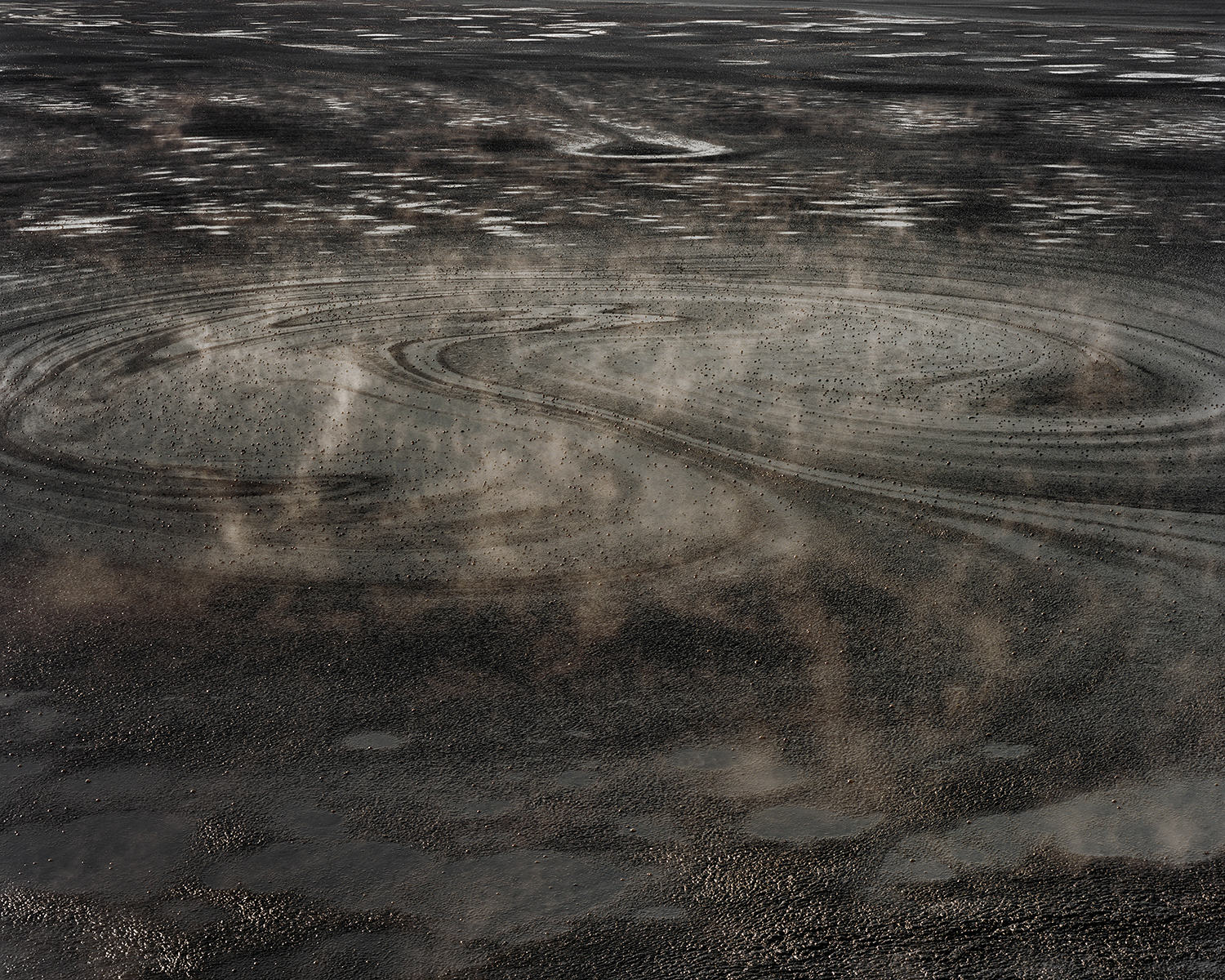

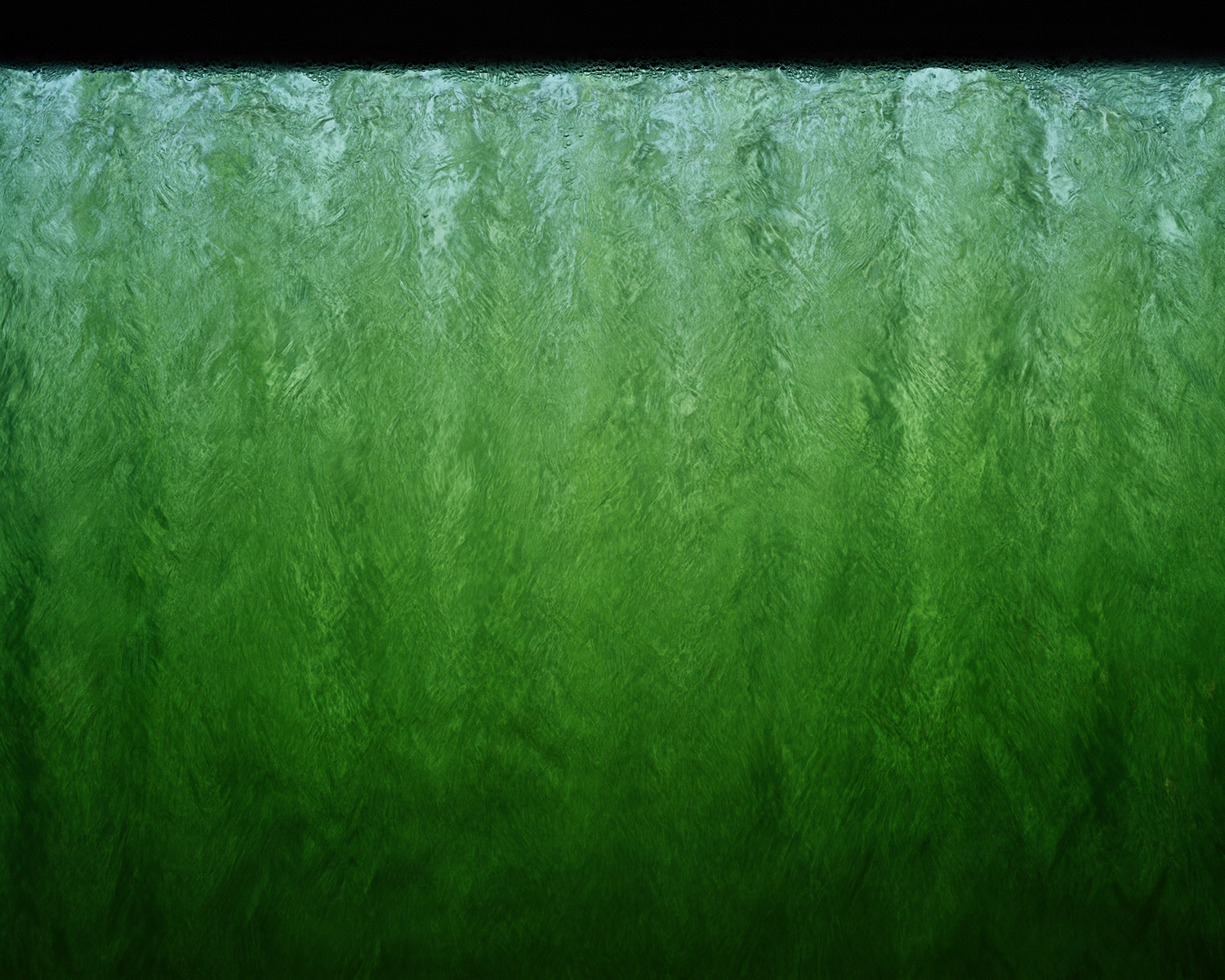

In this episode of Engineering Legends, we hear from Brad Temkin, a passionate professor and photographer who is fascinated by the impact of water on the environment. He recently published The State of Water capturing the visual and ecological beauty of the transformation of water at treatment facilities across the U.S.

See Brad’s photos, several of which are discussed in this episode.

Transcript

Kelly Rogers: Welcome to today’s episode of Engineering Legends.

Brad Temkin: Instead of looking on how we trample the Earth, I was more interested in how we fix things and that’s been sort of my career path for the last 20 or 30 years anyway.

Kelly Rogers: I’m Kelly Rogers and I’m here with Tiffany Long and in today’s world of social media, we are bombarded with images at an unprecedented pace and photographs really connect us to people, places, feelings, and stories, and in the water and wastewater business, it’s sometimes really hard to see the beauty in our infrastructure and to evoke those positive feelings. In fact usually they’re negative, particularly wastewater where someone who isn’t in the industry probably doesn’t think that a treatment facility is beautiful or awe-inspiring. And because of that predisposition, it’s really unusual for someone to really see the beauty and understand the impact, which is why I’m super excited about today’s guest.

Tiffany Long: I really am too. Today, we are joined by Brad Temkin. He’s an American photographer who is known for using his photos to document human impact on landscapes. Brad teaches photography at Columbia College in Chicago and his photographs have been featured in numerous magazines, including Time, European Photography, and Aperture. And he has work included in permanent collections at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Contemporary Photography. Brad has published numerous books, showcasing his photography. And for this episode of Engineering Legends, we’re going to speak with him about his most recent book, The State of Water published in 2019 by Radius Books.

This book features a collection of truly stunning images of the processes and structures that facilitate the movement of the water cycle, including drinking water, runoff and wastewater. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship for this work, which was featured in exhibitions at the Field Museum in Chicago in 2019, and at the Houston Museum of Natural Science in 2020 and 2021. After seeing his work, we became interested in knowing a little more about what hit drives him and how he found his way to photographing the plants and infrastructure that we are so familiar with in our industry, so necessary but often hidden. Welcome to this show. Brad, why don’t you go ahead and tell us a little bit about yourself.

Brad Temkin: So I started photographing as a kid in high school and I found that it was a tool for self-expression. I’d always been interested in photographing landscape and water was the first thing that I was able to really stare at without getting bored. And so I’ve been photographing water since I started making pictures, but when I started to make pictures, I was a rock and roll photographer and that’s what I did in the ’70s. And it got kind of bored for me. I mean, it was a lot of fun, but the pictures all looked the same and I’m interested in change. And so I saw, ended up seeing this person’s work, Minor White, whose work really kind of took my breath away and it was the first time I realized that photography could be like a poetic kind of thing. And so anyhow, I went to school at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio.

And I got my BFA there in 1979. And then I got my master’s degree at University of Illinois in Chicago. And I went there specifically because to study with a person who did a bunch of his work with water, because water was such a big part of what I was doing. And I just continued photographing the landscape. But as I photographed the landscape, I realized that people are everywhere and our impact on the land is very heavy. And I was interested in kind of looking at our impact as focusing on that. I just, I like the way people fix things.

Tiffany Long: Well, how did you get interested in specifically photographing wastewater?

Brad Temkin: So I had been photographing water and for a long time, but my focus was pretty much on, I was interested like I had mentioned about the impact on the environment and I was also a gardener. And so I had been photographing gardens because this was something that was interesting to me. And I did this project called Rooftop in where I photographed green roofs around the world. And I realized that we actually plant these gardens and these green spaces, not just to sit and meditate and relax and entertain, but also to mitigate our carbon footprint. And as I photographed, I learned that some of the things that we were doing with green roofs was based on storm water management. And so it made me wonder what happens when there’s too much rain in these impervious, this concrete jungle, and where’s it go?

And usually what would happen is it would go into our drinking water. So a lot of times the sewage would overflow into drinking water. So I got interested in that and in the infrastructure. And then I saw this film called the Big Short and it has nothing to do with water, but it had to do with the problem with the savings and loan and the mortgage overlending. And at the very end of it, the person who kind of discovered this, Dr. Martin Burry had talked about what he was doing. And it said that he was putting all of his resources into water. And at that point I was interested in infrastructure. And since I lived in Chicago, I was interested in getting into the deep tunnel. And so I contacted some people and I was able to get into it.

And I just found that wastewater is something that we never think about that, where’s it go? What happens to when you flush the toilet? What happens to the things that you flush down the toilet? And does it just go into like a magic garbage can or what happens? And most people don’t ever think of that, but what happens as it goes back into waterways, it goes back into our drinking water. And my past work on sustainability kind of brought me back to that. And I realized that what goes into the Earth goes back into us, and what comes out of us goes back into the Earth.

And so I was in interested in that. And when I began to research that and found that wastewater was didn’t magically disappear, but it magically became new water that we used that we would reuse for drinking and for other things like agricultural. And I realize that in Chicago, we have where I live, we have one of most incredible combined sewer systems in the world. And there’s over 700 different cities around that use combined sewer systems. And so I was interested in learning about that. And that’s how I use my photography is to learn about a subject I’m interested in.

Kelly Rogers: So was Chicago your first site where you went and filmed wastewater?

Brad Temkin: It was, it was a first site. I knew somebody, an engineer, who worked on the deep tunnel and I asked him if he could introduce me to somebody and he did, and I didn’t reach out to them until the light bulb kind of popped up in my head. And when I did start, I started with the deep tunnel and a couple of Chicago’s wastewater facilities, the O’Brien Plant and the Stickney Plant to name a few. And it was really interesting to me because like rooftop and like green roofs, what we do is we mimic nature in order to kind of in order to fix things because nature does that automatically, but it takes lots and lots of years. And so it was interesting to see that we did the same thing with the microbes and the filtration using sand and gravel and light, ultraviolet light to disinfect things. And I liked that we were using those things. And so I started in Chicago. I start everything in Chicago usually because that’s where I’m from.

Kelly Rogers: I think a lot of people don’t realize how beautiful some of those old tunnels are. Can you talk a little bit about what you saw down there?

Brad Temkin: Well, in the tunnels that were offline that you would say hadn’t been used yet. It was really interesting just to see how they blast in Illinois, we’ve got all this limestone and so they would go maybe 400 feet below and they would blast it. And then what they would do is they would kind of sculpt out and then they would put some sort of not membranes, but they would build an inner skeleton per se, to house the water and they would use that so it come out and it’s pretty brilliant because when things, when the tunnels they’re winding around and it’s almost a cave because it’s chiseled out and it’s really well done, but it’s interesting because they figure out how to kind of hold the water in a holding place and then when they’re ready to go ahead and start to purify it, it goes into the wastewater plants.

So I did see them before they went online and when they were offline to be repaired, which was pretty interesting to me. But what struck me was how simple it was, it’s just so it’s just a very simple I mean very simple way of approaching it for something which is really complicated that most people don’t ever think about.

Kelly Rogers: I’m really impressed that you know all the water wastewater lingo. You speak like you’re one of our engineers!

Brad Temkin: Well I learned, I mean, this was the thing that when I do a project, I become immersed in it and you have to learn those things because if you don’t you can’t talk to the people who are building it. And so even in my book I had put a glossary of terms so people would understand what effluent was or what the oxygenation was and why there was aeration and what not. And it was just really interesting to learn about and it just it’s, these things are so simple that you never think about them, but engineers put them to work and they make them where it just follows the laws of nature.

Kelly Rogers: Yeah. Wastewater is certainly one of those taboo topics that people just don’t want to talk about and don’t want to think about.

Brad Temkin: Yeah, I always get the questions like, “Did it smell?” Those kind of things. And it doesn’t really, I mean, there’s some spots that smell, but the dangerous stuff is the stuff that doesn’t smell that’s when it’s dangerous. Otherwise if it smells that just means that it’s water, I mean it’s alive.

Tiffany Long: So then how did you keep going to photograph different plants? How did you choose the plants? And is this something that I saw that you had been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship work? So how does that work?

Brad Temkin: Well so the way I chose the plants that I visit, the way I got interested in different cities was to find out what they were doing, how they were meeting the challenges of wastewater and drinking water and replenishment. And so Seattle has got an incredible watershed so I was really interested in that and a friend of mine in Chicago, actually one of the commissioners from MWRD had introduced me to Mami Hara. And when she had heard about what I was doing, she was interested and she said, “Yeah, come out here and see it.” I got interested in Phoenix because of the challenges they face with drought and the hundred year drought that they’re facing. And so they have to sit there and figure out how they’re going to replenish their aquifers.

And Kathryn Sorensen was doing some things that I thought was interesting. So I researched her in Los Angeles. You hear about the aqueduct and the long history of water and bringing it. And so that’s why I chose that and Philadelphia because it’s one of the oldest cities and I love Philly. And actually I called back commissioner cold Debra McCarty and who’s just an incredible person. And all of these people, a lot of the commissioners and people that got higher up, they started from the bottom and they learned their way up. And there was such a sense of collaboration in the industry that was sort of, that really got me turned on. And I got very interested in it. So when I went and the Guggenheim is this award that it’s a once in a lifetime award.

And what it is, is to kind of celebrate a person, whether it’s an artist or an ecologist, or an economist, or a scientist, or an attorney who has been doing something that’s been important in their field, and then what they’re doing, what they’re planning on doing, what they’re doing at that moment and what the committee or what the foundation thinks will be something that’s significant in the future. And so they support that and then what they do is they give you the resources, which is pretty much money to go ahead and take time to just concentrate on that. And my project proposal was to talk about the magic that happens in the transformation from sludge to pure. So it was amazing to me to see that toilet waste, shaite and urine and all kinds of ugly, terrible things that we wouldn’t be near it gets replenished.

And there’s this magical transformation that happens before it becomes clear and drinking water. And I thought that if I could kind of show that or show the beauty and the surreal quality of it visually, I would seduce people into learning about water. So they could then make their own decision. Because my philosophy is that information is what gives power and when people have information they usually make the right choices, but if they have bad information, which we see every day on Facebook and those kind of platforms, they don’t make intelligent decisions. So my intent was to get people so interested in water and wastewater use and that I would become an advocate for conserving water, which is something nobody ever thinks about. I mean, we don’t think about water, we don’t think about oxygen. Without those two things we wouldn’t be around. In fact, when people go looking for in the planets they’re looking for water. And the reason why they look for water is because where there is water, there is life.

Kelly Rogers: Have you gotten feedback from people who have viewed your photos or read your book where you’ve opened some eyes, or people have said, “Wow, I didn’t understand that.” Or, “I didn’t realize what was happening.”

Brad Temkin: Actually. Yes. From people in the industry and people outside of the industry, the people outside of the industry, they just say, “God, I never thought that that could be beautiful.” I never thought that sludge or that feces would be interesting to look at, but beauty is my sharpest tool. So I use that to get people to look at things because you’re not going to look at something that’s ugly. You’re only going to look at something which is attractive or shocking, and I’m not really the shocking kind of person. And then people in the industry,it really it gave me a lot of satisfaction. They thanked me, people would thank me. And they’d say, “I see this every single day and I never looked at it like that. And it’s so nice to see somebody celebrating something that we do, which is so important, but so under appreciated.” And so by bringing attention to the ecological beauty of this process, I think that that’s what they appreciated a lot. And then they would look at my pictures and they’d go, “How do you see this stuff?”

I remember being in Chicago at the Jardine Water Treatment Plant for drinking water, which is very high security. And I had told every city I said, “Look, you can look at my pictures because I don’t want to have any sort of security issues.” And he followed me and was walking around. And when I set up my camera, I made the photograph and I said, “Hey, would you like to see what it looks like in the camera?” And he is like, “Sure.” So he puts a focus cloth over his head and he goes and looks at the camera and he comes out from underneath the cloth and he just shakes his head and he goes, “Brad, I don’t think we’re going to have any problems with your pictures.” Because I was looking at forms and shapes and kind of relationships and color and those kind of things. I wasn’t interested in showing the workings of pipes and machinery, because to me, that’s something which is foreign to me and not very interesting actually. I was more interested in the abstract quality that was there.

Tiffany Long: Well, I’ve got a copy of your book sitting here and the photos really are quite beautiful.

Brad Temkin: Thank you.

Tiffany Long: So when you go into a plant, do you have somebody that usually accompanies you?

Brad Temkin: I usually do for when I go. Some cities are different than other cities, but usually I would be accompanied into the plant. And then as they got to know me, they would sort of leave me alone and just say, “Let me know when you’re ready to come out.” When there was a confined space, I needed to have someone with me, of course. And I was trained to go into those spaces, how to use the meters and kind of what to watch out for. But at the same time a lot of people if they didn’t know me, I was accompanied all the time, but it didn’t bother me because they just would let me do whatever I wanted anyway once they vetted me and saw that I was okay.

And they wouldn’t have allowed me in the plant, if they didn’t think that I was okay. If they thought that I was not sincere, and if they weren’t interested in what I was doing, they probably wouldn’t have given me permission in the first place. But yeah, I also enjoyed having someone with me because I could ask the questions about things like lingo and like what does this do? Why is this here? What happens if it’s not there? And those kind of things. So it was weird being in a sewer or whatever.

Kelly Rogers: Yeah. So when you go into a plant, you’ve been in quite a few now, do you have favorite components of the plant or architecture that you’re like, “I love to photograph that particular element.”

Brad Temkin: I don’t have any sort of preconception because the way I make pictures is it has to do with the moment that I’m in. It has to do the moment of light, when there’s good light or if there’s not good light, it has to do with what I’ve photographed before, because I don’t ever like to repeat myself. But to give an example, when I was in Chicago, I photographed an empty aeration tank and it looked like piano keys. And it was really interesting to me, it looks like a, in an aquarium, the fish tank on the bottom, the filtration so it’s got those sort of piano key kind of filtration. When I was in LA by Hyperion, there was an empty aeration tank and they were discs. And that was really kind of interesting to me. So I had asked I said, “So can I go down there?”

And I went down the ladder, I brought my equipment with me and I’m literally walking on pipes with my equipment because you couldn’t really walk down in the soot. Well you could, but you really didn’t want to. And I balanced on the pipes and I set my camera up and actually the person I was with, she photographed me from above because she wasn’t going down there. I’vegot my hard head on and everything. And so when I see a different aeration tank, I want to photograph that because it’s different. But I don’t know, I don’t do research into what the plant has because most of the plants have got the same components. They’ve got effluent tanks, they’ve got aeration tanks, they’ve got the second effluent and those kind of things.

So I mean that’s all pretty much the same process. They just do things maybe a little differently. They might have, one plant might have been newer than the other, so they have different equipment, but it does the same thing. And it just depends at the moment when I see it, I’ve seen an effluent tank that was flowing and it looked like a zen pool and it was really, really peaceful and interesting. And the way I photographed it was like a zen pond that was how I made the picture. So, and then there’s one picture that I was in Philly and I went to this old sewer is a Mill Creek Sewer and it’s one of the oldest sewers, it’s all brick.

Kelly Rogers: Oh yeah. I think I saw that some of those photos.

Brad Temkin: Yes. It’s the first one in the book actually. And what was interesting was the light that was coming down, they wanted to lower me down that to get into this sewer. And I was like, “No, that’s not happening.” Because I was] going to be in a going around in a harness. So what we did was we found another opening and I climbed down and I walked through the sewer to that spot. And then they lowered my camera equipment down from where they were going to lower me down. And it was such a magical moment that that’s what I photographed – that light coming in. And it was a kind of amazing really the light that was happening and just to be able to see the brick and everything and where it was, you weren’t sure what it was, but as soon as you see sewer, you go, “Oh wow. He’s in a sewer?” And-

Kelly Rogers: Yeah. Those brick tunnels are just beautiful. I love the old brick tunnels. Yeah.

Brad Temkin: Yeah. They are great. They really are.

Tiffany Long: Yeah I like that you’re using art to educate people. It’s great.

Brad Temkin: Thanks. Thank you.

Kelly Rogers: So do you have a favorite plant that out of all the ones you’ve looked at or the different locations you’ve gone on?

Brad Temkin: I have a few favorites. O’Brien in Chicago is one of my favorite places. I really like that because it has everything, the screening room where they screen all the garbage is really interesting. The ultraviolet light disinfection area is, and it’s one of the only places that do that, because most of the time they use chemicals and I just like everything about that plant and it was pretty easy to get around. I loved Los Angeles in Asilomar with the shade balls and that’s a purification plant not a wastewater plant. But the Hyperion is pretty cool. And I really love in Philadelphia, I thought Philly had some great plants and one of the plants where they housed the pure water, the water that right before it goes into the chlorine before it comes to the faucet, it’s covered completely.

And when you open the door, it looks like you can walk on the floor. But actually, that floor is just the water and is about 20 feet deep so you can’t. If you dropped anything, if I dropped a lens cover in it or if I sneezed or whatever, they’d have to drain all that water because there’s no bacteria in it. So they would have to repurify that water to get in. But the other plants in Philly, I mean, Philly’s got some really incredible plants and I really enjoyed working in Philadelphia too.

Tiffany Long: Nice. So do you have a bucket list of locations that you still want to shoot?

Brad Temkin: Well, I would like to do some more work in New York. I’d like to do some work in New York because of their underground facility. And it’s also probably the longest place between the Catskills and drinking water. I think that’s really interesting. Los Angeles, I’m really interested in the aqueduct which I’ve been doing lately. I’ve been photographing the aqueduct and that, and I also want to do a bunch of wastewater down by New Orleans and because of all the flooding that’s been going on for a long time, the way they’ve been dealing with it is, is pretty extraordinary. So New Orleans is on my bucket list. New Orleans and New York are two places I want to examine a lot more. The whole I-10 corridor is really interesting to me from Los Angeles to Florida, that whole bottom part of the corridor and how they deal with the whole notion of storm water and water management has been kind of a topic in the back of my mind for bit.

Kelly Rogers: Yeah. Certainly a different animal down there than it is on the west coast. Completely different issues for sure.

Brad Temkin: Completely different. But still the drought, I mean it’s not drought, but yeah it is.

Kelly Rogers: Yeah. I’m guessing along the way, you’ve met a lot of interesting plant operators. Sounds like you interact with them a lot when you’re taking photos. Do they tell you a lot of stories about the plant and the history? What kind of relationship do you develop with those folks?

Brad Temkin: They do. They talk about their history, which I’m really a good listener. And then when they tell me about what was before. In Houston they’re building the largest, I think it’s going to be the largest wastewater plant in the country. And that’s been really kind of interesting what they’re doing in Houston as well, because they have the flood and the drought kind of problems to deal with, but where they put it. But yes, I do, I talk with these people a lot and I listen to them I do more listening than talking.

Kelly Rogers: Yeah. We talk to a lot of the operations folks just in our job and in doing the podcast. And it’s amazing that most of them have been there for almost to their entire career. And like you said earlier, they kind of grow up at the facility and they work their way up. And we just talked to somebody a couple weeks ago. I think he had been there 40 years working at that same plant and just so dedicated to their mission. And they see it as a mission of creating clean water and helping that water cycle.

Brad Temkin: Yeah they love it. And when my show actually went to Houston, one the things I have asked the museum to do was to give access to the people that actually worked in public works so they could see it as well. And one of proponents of the exhibition was to show where the sewage goes and how it becomes clean and the water source and how the two things kind of intermingle, they don’t intermingle until they’re clean. But in Chicago we get our drinking water from Lake Michigan and the sewage and combined sewer system gets purified and it goes back into the Chicago River, which has been engineered to go away from the drinking water source. However, that source becomes, or that river becomes the drinking water source for New Orleans and Mississippi and because it goes downstream and that’s pretty interesting because that’s a responsibility that Chicago has to the south of us. And so it’s good to see that they rise up to that occasion.

Tiffany Long: Yep. We’re all connected that way. That’s for sure.

Brad Temkin: Absolutely. We’re all connected. And that’s what sustainability is all about – actually it is not about making things clean, but realizing that what goes in comes out and it just needs to keep circling around. Otherwise we die and I’m not talking about us as humans I’m talking about anything, once it stops it’s the cycle is over and it just dies. So this is what sustainability is – about resilience and keeping things alive.

Kelly Rogers: Brad, we just really want to thank you for your time today. This was fascinating. It was great to hear that you love water just as much as those of us in the water and wastewater industry. So we really appreciate your time today and you telling us your story. It’s been great.

Brad Temkin: Thank you very much. Thanks for having me.

Kelly Rogers: We both really enjoyed hearing Brad’s stories today. I know Tiffany already has his book like she mentioned, and I’m definitely going to pick up a copy as well. It’s really been such a joy to see the facilities that he photographs through his eyes and to really understand his motivations and how he goes about picking those facilities and what he actually photographs.

Tiffany Long: I bet many of our listeners out there have their own engineering legends. We’d love to hear from you. Please send us your feedback, stories and ideas for future episodes. You can reach out at info@brwncald.com. This podcast was brought to you by Brown and Caldwell. It’s our purpose and our passion to safeguard water, maintain infrastructure and restore habitats to keep our communities thriving until next time.

Tiffany Long

Tiffany Long Kelly Rogers

Kelly Rogers